The impact of digital health evolution in cardiology practice

21 January 2014 / 11:11 am

Cardiology practice has been at the forefront of digital health technologies for more than a decade. As cardiologists, we have become familiar with the use of digital systems for cardiac imaging, guiding coronary intervention and with sophisticated digital mapping equipment for electrophysiological studies. We have a myriad of digital diagnostic techniques available for recording and storing electrograms as well as highly complex implantable device technologies. There is no surprise therefore that many of the key physicians leading the development of digital health technologies around the world are cardiologists.

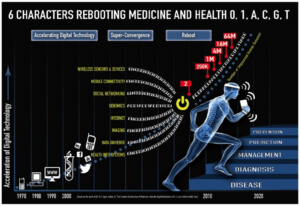

The rapid evolution of computing technologies, and in particular, the uptake and complexity of modern smartphone technology has meant that over the last few years the world of digital health has started to advance even more rapidly. High-powered smartphone technologies, miniature hardware sensors and network connectivity allow us to record, store and share an enormous amount of health-related data.

It is estimated that there are 1.75 billion smartphone users in the world and around 100,000 mobile health applications available for download. Large companies such as Apple, Google, Microsoft and Samsung have all put digital health at the core of their business development in 2014 and have launched platforms to try and entice new users as well as new software and hardware developers. The financial impact of this is enormous. Worldwide revenues from sports, fitness, and activity tracking devices are expected to be worth $1 billion in 2014 and sales are predicted to grow by nearly 50 percent by 2019. As a consequence, venture capitalists are targeting digital health software and hardware start-ups for investment.

Social media has been an important part of the digital health revolution. It would be unusual for a digital health start-up to not have a strong online presence and run and maintain their blogs, social feeds and other channels. Many cardiologists have embraced these social media technologies as a vital part of patient and community engagement. The LinkedIn group “Digital Health” has grown in just five years to a community of over 30,000 digital health professionals. Vibrant discussions and posts are helping to shape the announcements, developments and funding of innovative digital health technologies.

Alongside this technological transformation in software and hardware, patients are starting to demand greater access, involvement and control of their own medical and personal data. A survey of users across all age groups revealed that over 75 percent want to use their own digital health technologies. Patients are now starting to measure and record more of their own personal health information as part of the “quantified-self” movement. Thanks to new data acquisition technologies, people are able to measure multiple modalities of their daily life, using devices such as wearable sensors, cameras, data-loggers and GPS. A recent report from Price Waterhouse Coopers (pwc.to/1tdMfP2) suggests that one in five Americans owns a wearable device and 10% use them daily. Most people buy them to help them exercise more but the majority of the people surveyed used them to collect and track medical information. High powered computing systems such as IBM’s Watson are starting to analyse the “Big Data” that these and established clinical devices are generating, potentially allowing computers to start providing more accurate diagnostic advice and early warnings of impending clinical deterioration.

Person centred health records, or patient portals, are allowing patients to upload their health data onto customisable, editable platforms enabling them to share their medical history with health professionals of their choice. As network connectivity speeds up and cloud storage becomes cheaper, systems will start allowing patients to maintain their own databases of not only their medical notes, but their medical images, x-rays, cross sectional images and ultrasounds. These portals often link into external discussion sites and some have their own patient forums. Websites for patients such as www.patientslikeme.com permit an even greater understanding of medical conditions, allow patients to communicate with other people with similar illness and direct them towards new treatments and, occasionally, new doctors. Some websites have taken this one step further and provide online rating systems for physicians so that future patients can read reviews of practice.

Patients have been familiar with recording blood pressure, pulse, height and and weight for years but the technology now exits to transfer this information electronically directly to your doctor. Wearable technologies and smartphone devices are increasingly allowing us to remotely diagnose and monitor patients. The AliveCor (CA, USA) hand-held ECG is a small portable device that attaches to a user’s smartphone and records a high-quality single channel ECG.

The recording is stored in the user’s cloud account or linked to their doctor’s account. ECGs can be remotely analysed, emailed or printed for clinical interpretation. The software now also has an FDA approved algorithm for the detection of atrial fibrillation. This type of technology allows a rapid diagnosis for patients with symptoms of palpitation that would otherwise need prolonged monitoring with Holter ECGs and event recorders. It also allows for more remote follow-up of patients with complex arrhythmias who can discuss their symptoms over the telephone or Internet whilst sharing their traces directly with their electrophysiologist.

Community care and patients with chronic diseases are starting to benefit from home digital health technologies that can track and map clinical parameters, highlighting to their physician or caregiver when parameters change. A number of different telehealth and telecare pilots are underway to determine if these systems can keep people at home, reducing hospital admission, and improving patient outcomes, particularly in chronic heart failure, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Some novel community services such as the Call and Check service in Jersey are de-medicalising care further, with visits and checks provided by postmen.

With patient data, images and clinical information stored on the internet, technologies are now developing that allow us to consult with our patients using network video. Patients can choose to have a consultation with the physician of their choice at a time that suits them from the comfort of their home. Smartphone based software such as Babylon (www.babylonhealth.com) and HealthTap (www.healthtap.com) might have the same effect on face-to-face medical consultations that online retailing has had on high street shopping. Why would empowered patients who control their own data wait to consult with their local specialist when then can choose the one that they want, anywhere in the world, at a time that is convenient to them?

There is now doubt that we entering a new era of digital health technology where patients will have greater control over their health information and their choice of health provider. Internet and network technologies mean that geographical locality is no longer a barrier to high quality care. In a health conscious world of wellness, an important goal of the quantified-self or digital health movement is to modify peoples’ behaviour to bring about health benefits. In order for that to happen, the user must be offered information into their data that is motivational and achievable. The hope then is to steer people to longer and healthier lifestyles whilst helping them manage their time better and track and preserve life memories.

Today patients ask their doctor. Tomorrow they may ask their data.

10 key impacts of digital health evolution on cardiology practice

- Patient controlled data

Online patient portals allowing patients to store and curate their data whilst controlling who can view their health data.

- Patient generated data

Health trackers and devices that allow patients to collate their own independent health information for feeding into #1.

- Online video consultations

Convenient secure online systems allowing patients to get instant access to medical advice.

- Implantable device technologies

Devices such as implantable electrogram loop recorders, injectable monitors, patch biosensors allowing patients to choose the type of information they wish to record for #2.

- Application derived diagnostic algorithms

Complex software algorithms providing medical diagnosis based on information provided by #2 and #4.

- Remote monitoring and diagnosis

Wearable or insertable device technologies that transmit to health professionals for continuous monitoring and analysis.

- Online pharmacies

Drug prescriptions and deliveries remotely without direct physician input based on patient data and #1-5

- World access to medical advice

24/7 availability of networked, high quality medical and nursing specialists using online video technologies.

- Patient communities

Online social sites for patients to share information, discuss cases and identify new treatments and specialist physicians.

- Medical education

Streamed, live cases with interactive discussion with clinicians. Online case reviews and advice. Worldwide access to peers and new opinions.

More Posts

7 May 2025

A digital health diary revisited

16 March 2024

Developing a new strategy for healthy Islanders

4 February 2024

A digital health diary for Jersey

27 December 2022

Utilising artificial intelligence in cardiology practice

12 June 2022

Under the bonnet – time for your heart’s MOT

12 March 2022

What is heart valve disease and what does that mean for me?

12 January 2022

Preventing heart disease using augmented digital health intelligence

1 October 2021

How heart health has been impacted by COVID-19

1 August 2021

The importance of the rhythm of your heart

21 June 2020

What is atrial fibrillation?

8 April 2020

Coronary heart disease and risk of heart attacks

11 January 2020

The Era of Immersive Health Technology

22 September 2019

The heart and stress

18 August 2019

Screening for Atrial Fibrillation and the Role of Digital Health Technologies

20 November 2018

Ectopic beats – how many count?

28 July 2018

How can immersive VR and AR technologies improve your physical and mental health?